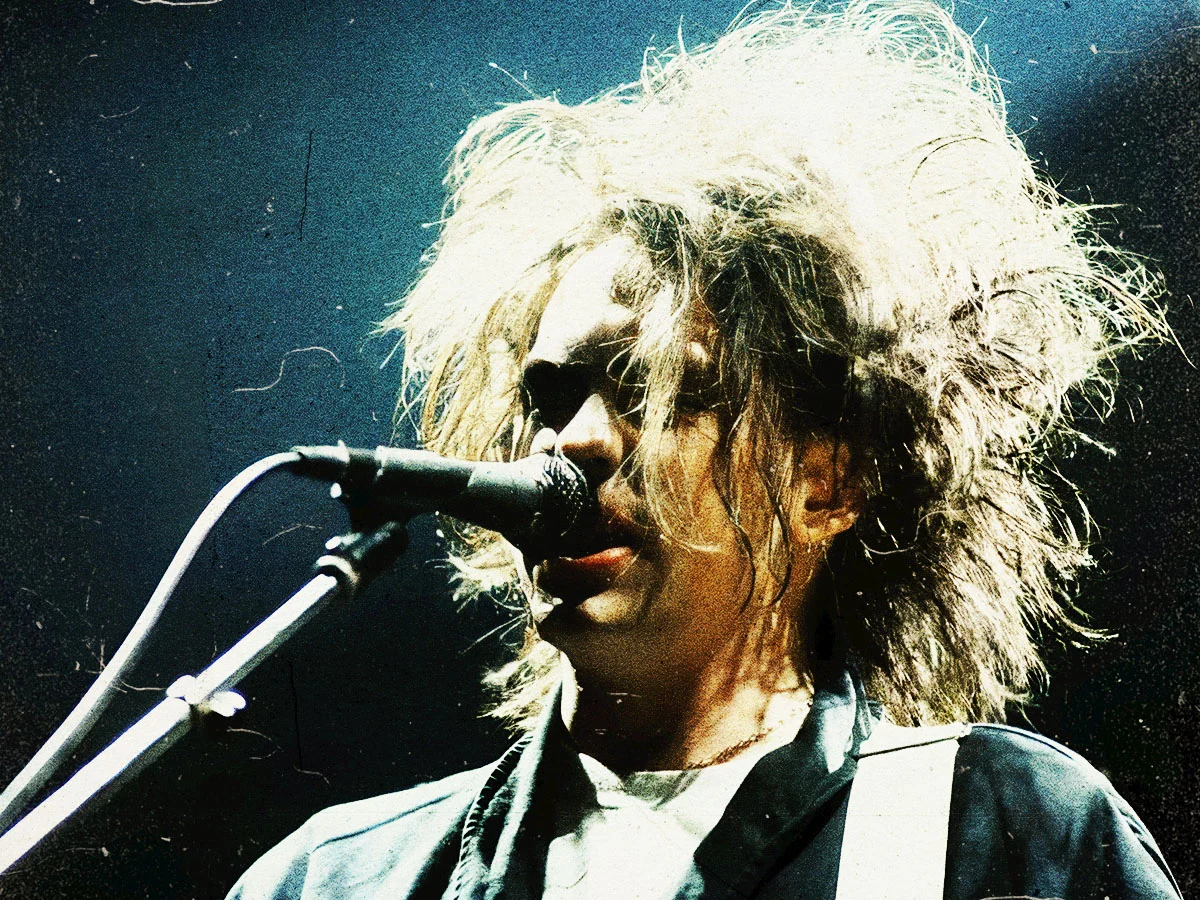

The novelist Graham Greene once wrote: “There is always one moment in childhood when the door opens and lets the future in.” For many of us, that Promethean juncture, where the surface of the world unzips and reveals a sense of depth and identity beneath, occurred at the hands of David Bowie. The Cure’s Robert Smith was no different.

“I listened to music before Bowie, obviously,” Smith told MTV. “I have an older brother, and he played me [Jimi] Hendrix, Cream and Captain Beefheart… all that type of stuff from the 1960s, but David Bowie was probably the first artist that I felt was mine. He was singing to me.” Not only was young Smith a fan, but the quirks of Bowie’s artistry also proved an inspiration. “I always loved how he did things as much as what he did. I love that idea of being an outsider and creating characters,” Smith says.

By crafting this otherworldliness, Bowie, by virtue of his creative idiosyncrasies, illuminates a brighter reality. As Dougie Payne of Travis recently explained regarding the wallop of The Starman: “The only way I can describe it is like all the lights came on. You’ve got this incredible range from epic songs to small songs, and it was almost like it gave you a window into another way of living, a more bohemian way of living.”

Countless stars have concurred. The triumph of Bowie is that you’re not just a fan of Bowie’s music—you’re a fan of the concepts, the artwork, the market stalls that sell Bowie trinkets, the bars emblazoned with Alladin Sane lightning bolts. Hell, you’re not even just a fan of Bowie and the whole oeuvre that goes along with him—you’re likely a fan of Scott Walker, Viz, Yukio Mishima and sushi; all the amazing things that he introduces you to. In a manner that The Cure have since emulated, he might be termed alien, but in actual fact, he sharpens the focus on the everyday.

For Smith, one record, in particular, arrived on what could’ve been a humdrum day and suddenly rendered reality a little more vivid. “David Bowie’s Low is the greatest record ever made,” he told NME in 2013. “I bought it on cassette and the same day I went to a garden centre with my mum. I’d ordered it from the local record shop, and Paul, who was in the band, and is my brother-in-law, had dropped it through the letterbox. It’s like one of those weird days.”

He wistfully recalled: “I walked home from school, there was the cassette and we had a cassette player in the car. I went with her to a garden centre, and I listened to Low while she went and did whatever mums do in garden centres, and I was like utterly, my whole perception of sound was changed.”

His hair suddenly shot up, and eyeliner began to float around his conscious, if not the eyes just yet. Smith was enamoured. And the world was more varied and full. As he explains, “Just how something could sound completely different, like ‘Breaking Glass‘, everything on there, in fact, ‘Sound And Vision‘, everything on there, everything I heard was astonishing, really astonishing.”

It was the creative expansiveness of the album that proved mind-altering more so than emotionally connective in a resonant sense, as he explains: “When I put it on now the sound, dunk dunk, everything is just fucking genius! There are other albums that I love much more, like viscerally much more, like Axis: Bold As Love, or Five Leaves Left, albums that I can cry to, but Low was the album that had a huge impact on me, just how I saw sound. No other album has done that to me.” Even his nemesis Paul Weller agrees on that.

What does Low say about David Bowie?

Low arrived at a time when Bowie was searching for a fresh start personally. He had always done this in a creative capacity, but his last venture as the Thin White Duke has pushed his sanity to the limits. Now, he was holed up in Berlin, determined to walk the tightrope of achieving sobriety while staying artistically daring. Thus, the next chapter for Bowie was almost fated to be an exploration of sound. In truth, this comes from the same central tenet of “being an outsider and creating characters” that first attracted Smith to Bowie.

During this period, he slept with a painting of the Japanese novelist, actor, and nationalist civilian militia, Yukio Mishima, over his bed. This love for Mishima and the kinship of ‘the mask‘ that they shared perhaps offers the finest insight into how Bowie viewed his own character art and, ultimately, how that sense of mystery, androgyny, and sense of vivifying reality by going beyond it inspired Smith’s own work.

I recently spoke with the expert on all things Japanese culture, Roy Starrs of the University of Otago in New Zealand, who explained: ”In the mediaeval Japanese Noh theatre, the actor spends some time before he goes on stage staring at the mask he is about to put on, which may represent either a male or a female character, since both were played by male actors.”

Continuing, he added: ”This ritualistic moment of contemplation resembles a Shamanistic rite of spirit possession, in that the actor intends to shed his own identity and take on the identity of the character he is about to portray. Mishima was fascinated by this profoundly mystical form of theatre – he even wrote ‘modern’ Noh plays himself – and one might say that he lived his life accordingly, continually shedding his ‘own identity’ and very consciously putting on one mask after another, as if no single role could ever quite satisfy him.”

Adding: ”If anyone were to ask, ‘what then was his own true identity?‘, I would refer them to Mishima’s autobiographical novel, Confessions of a Mask. That paradoxical title says it all: the gay sadomasochist he presents therein for popular consumption as his ‘true self’ was only to be regarded as another mask.”

And conbcluding: “If that ultimate mask were ever removed, one would find perhaps not any permanent or solid identity but that creative emptiness out of which, the Buddhist philosophers tell us, all phenomena arise. Bowie, of course, was a very creative shapeshifter himself, so it is not surprising that he understood all this about Mishima and valued him as one of his very favourite writers.”

What does loving Low say about Robert Smith?

While Smith might not shape-shifted in the same sense as Bowie or Mishima, it is evident that The Cure has always looked to poke beneath the veneer of society’s own mask. Whether it be the feverishness of ‘A Forest’ or the simple euphoria of ‘Friday I’m In Love’, Smith’s work achieves the artistic goal of vivifying reality. The exploration of sound on Low epitomises this profound playfulness and happy knack of not playing to the gallery.

This is perhaps why The Cure has never stayed in a lane for too long themselves. As he says of the bands he has inspired, “I think they’ve been inspired in the same way that I was inspired by the way Bowie did things. I think younger bands are inspired by the way The Cure do their own thing and keeps going.” In fact, you can’t even rule out that they inspired Bowie himself, in turn. After all, the Starman invited Smith to perform at his 50th Birthday Celebration at Madison Square Garden, where they played ‘Quicksand’ and ‘The Last Thing You Should Do Together’. Nobody has checked in a while, but at the last time of asking it was clear the wild-haired frontman still had quite recovered from the show.